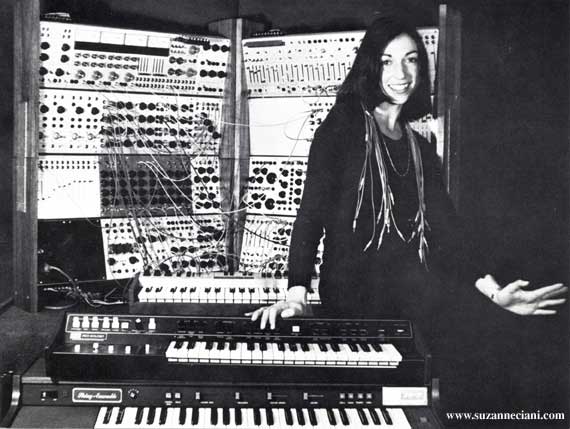

Interview with Suzanne Ciani (Part 1)

Post date:

Suzane Ciani requires no introduction. A five-time Grammy nominee and Indie Music Awards Winner, Ciani has been one of the pioneers in the world of electronic music. She agreed to an interview and we chat about her career, her favorite synths, her successes in the advertising industry, the film that was recently made about her life and much more. We had so much to talk about, it was impossible to summarize it all in one article, so we will be posting the interview in parts over the next couple of weeks.

What do you think about the Synth community?

I’ve been back into this world again and doing a lot of traveling and so I’m really impressed, I see these wonderful collections of vintage instruments all over the world. In Melbourne there is the electronic music studio there, then in Stockholm, EMS, quite amazing. And then there are private collections that you see. There is a fellow from Philadelphia, I don’t know his name off the top of my head, but he has a huge collection. So, I think that it is important that these instruments be collected by the right people. You know, by people who care about them.

You’ve received classical music training, what is it that got you into synthesizers?

Well, I guess I would say that I was in the right place at the right time. I had gone to graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, so I had come from the East Coast and went to graduate school in the West Coast and that was the place to be in many ways. It was in the late sixties, 1968, and I met Don Buchla there. I also studied at Stanford University with Max Matthews, who is the father of computer music. And I studied with John Chowning, who was at Stanford. And also, this was the location of the very first public access electronic music studio, called The San Francisco Tape Music Center. And so I could go to this facility, for $5 per hour.

What a privilege back then

Yeah, it really was. So I guess I was just in the right place. I was looking for it, because even on the East Coast, my evening class had an evening at M.I.T (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), that was our brother school and that was the first time that I heard of music technology. I didn’t know much about it and then, when I got to the West Coast, it just was just overwhelming. Buchla was the main excitement for me.

That’s great! How was it to actually have met Don Buchla? Did you meet him through your studies?

I met him through a boyfriend. My boyfriend was in the architecture department and his professor had a studio next door to Don Buchla’s studio. You know, big warehouses down by the waterfront, and so he said “I want you to meet my neighbor. And Harold Paris, who is an amazing sculptor, he worked in high-tech plastics. The sculpture world was also undergoing a revolution because of these new materials that were being used, injectable foams and polyurethanes, different kinds of plastic. And Harold Paris, who had been traditionally trained and was a great graphic artist and sculpture in bronze, started working in these media.

It was a time of upheaval, politically, with the Vietnam war. Nothing was the same, it was a very revolutionary historic moment in all areas. And I think that contributed to the openness to these new possibilities.

What did you think of the Buchla synth that you used when they first came out and why did you choose them?

Well, I just fell in love with it right away, there was no explaining it. The thing about Don Buchla is that he really was designing an instrument, an interface, something that would talk back to the performers, something that could be performed. So there was a lot of feedback in the machine. It wasn’t just a closed system, it seemed to be alive, it told you what was going on. It had a lot of lights, a lot of LEDs and little incandescent lights, that showed you the intensity of a control voltage. So, the machine seemed to have life and it was something that I developed a relationship with. In those days it was all very intuitive, nobody could study electronic music, there were no classes, not even any manuals. You just would be with the machine and spend time with it and get to k now it, so it was an organic process of discovery.

I think Don’s designs were particularly interactive. I also played a Moog back then, there was a Moog at the San Fransisco Tape Music Center, but the Buchla had more controls and it is a different design - because it was compact, the Moog used those big quarter inch cables and was huge, you couldn’t move it around. The Buchla came in a suitcase, you could choose to put it in a suitcase if you wanted. The cables were all color-coded and there were two different types of cables, so you had the banana cables for pulses and control voltages, and audio cables, little eight inch audio cables. It had a certain clarity of purpose in its design.

The euro rack systems of today, all those jacks are the same, all the cables are the same, and I grew up on a Buchla and that’s what I love. Now that I’m getting back to it, I’m having a lot of fun, it’s kind of like it’s more abstract because I’ve spent so many years in orchestration and writing for instruments and more traditional composition. Even though I use electronics to record my music, being back with the Buchla is very freeing.

You are there, sculpting the sound in the moment spatially. Buchla’s music was always spatial, from the very beginning he was a quadraphonic. In fact, I think he’s even credited for having developed the first quadraphonic system. I mean we just took it for granted, like you had four speakers, he had spatial control of the sound.

And today, let’s just say I won’t play without that. So for me the quadraphonic, the spatial character of the music, is just essential. It’s a set part of the music and it’s in my tech rider that I have the quad setup, but sometimes people don’t understand how essential that is.

It makes you feel like you are a part of the music and in-between it all?

Yeah, you are immersed and it gives it life. The essence of electronic music for me, anyway, is the movement of the sound, the way that it moves. It is not about the timbre per se, and I don’t use an additional keyboard. What’s magical about it is that earlier instruments, you could say that they had limitations based on the physical ability of the player and the instrument. How long could you hold a note, how fast could you play notes, how long could you hold your breath, what was the range. There were all those limitations and with electronic music, suddenly those conditions were gone. You could sustain a note for a month, there was no one who could do that before. You could have an instrument go below the audio spectrum to above the audio spectrum and it could jump, instantaneous. So it was a whole new world of sound that was out of the context of the limitations of instruments and performers.

Before that, music started to get more and more complex as players tried to prove how great they were and academic music became more complex, so that the composers could show how skilled they were. And in electronic music, all that was moot because electronic music made complexity easy.

It wasn’t so much about the players skill anymore?

Well, it was a new skill. In other words the goal wasn’t to make something difficult and the goal wasn’t to show off your playing ability, your virtuosity. The goal was to really discover new of moving sound.

A lot of composers of the time fixated on creating songs from from the past on the synth, but you took a different approach. Why?

Songs from the past were conceived in an instrumental world that was more traditional and the Buchla, which was my first instrument, I wasn’t interested in using a traditional keyboard. It was a whole new music that was possible, I have to say that a lot of people didn’t understand the new music. I have much better understanding for it today. In the late sixties, if I did an improvisation on the Buchla (and some of those have been released by Finders Keepers, the Buchla concerts 1975) people didn’t hear it, they didn’t have a listening for it, they couldn’t take it in and I was frustrated by the gap between my sense of music and my audience. When I finally went on to record my first album, it really was a combination of the new electronic music and my traditional classical background. I went back to melody and combined that with electronic techniques that were non-keyboard techniques.

And did people then find it easier to understand?

I think people found it easier to understand, but now what I notice today when I go out and I play, all kinds of people just love it. Even though it is very abstract and very unconventional. There are people who are in electronic music who can appreciate it, but there are even people who don’t know anything about electronic music who are willing to be taken on this journey of sound. So, I’m very encouraged that there is a new listening. It’s kind of like in visual art, where people initially freaked out when they first saw abstract art.

I love the analogy with visual art because it is so clear there that you have this representative vision and then you have something abstract and at first you don’t trust the artist. It’s like, “don’t you know how to draw?”

What is your favorite album that you have worked on or the most memorable one?

Well my first album, Seven Waves, was really important for me because that was my first. Over the years my second album was electronic, The Velocity of Love, and I added piano to the last song on that album and that became a big hit. The progression after that was that I started to add acoustic instruments. So, Neverland was the third album and that had a few acoustic instruments, History of My Heart had more acoustic instruments, and then I did a solo piano album, which was quite a surprise to me. I was so involved in electronics I thought that I would never play the piano again as a main instrument. And then it went all the way to orchestra and piano, so Dream Suite was 100% acoustic.

Now I’m as surprised as anybody that I’ve gone back to the Buchla. How did this happen? But it is a wonderful to reconnect, because I really feel that when this technology was new, these instruments, they didn’t get fulfilled completely. We lost the possibilities of those instruments the first time around and primarily because they were looking for a popular market, so they took a left turn. Instead of developing the new language and the new possibilities, they really just became keyboard instruments with some sounds that imitated conventional instruments and some sounds that were new. But nobody ever explored the interactive performance possibilities, which was what Don Buchla intended.

I mean there’s all kinds of electronic music. They are wonderfully suited to recording, tape recorders came along at the same time and you could make a sound, record it, you could edit it. Then you had digital recording and you could manipulate sound and cut-and-paste them and create pieces that way, but this special sub-category of live electronic performance, modular electronic music instruments. Don Buchla never used the word synthesizer because it was a loaded word. It was an unfortunate term because it sounded synthetic, like it really was something that was recreating something that already existed. It was synthesizing something and that was never part of the concept that Don had. And so he wouldn’t use that term and it was awkward, the electronic music instrument. He had some terms like the music easel and the electric music box.

Be sure to read Part 2 Next Week!